Jeff Poole digs deep in new book about Charles Stick's gardens

Orange County journalist discusses his new book and why he left the Orange County Review

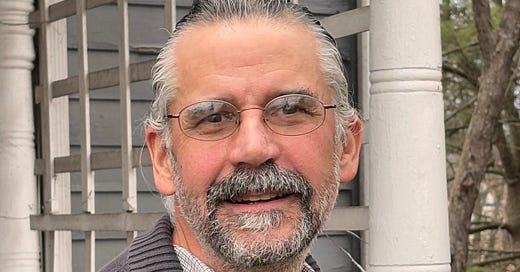

If you’ve wondered what former Orange County Review editor Jeff Poole has been up to since he left the newspaper two and a half years ago, you’re not alone. For 26 years, Poole, 54, was so reliably present at county meetings and local events—and his award-winning journalism and photos such a mainstay of community life—that his departure came as a shock …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Byrd Street to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.